A Guilty Man

Percy had been waking to vomit every night at 2:30 a.m. for six long weeks, the bucket on his bedside table as much a fixture in the bedroom as the snoring colossus he called ‘dear’, sleeping next to him.

Despite Margaret’s attempts to find him a solution, even with all the back-patting and gentle nursing, Percy suspected her of foul play. Evidence did not align with his suspicions; he had never caught her in the act of imperilment, and through various hospital and specialist appointments, he had long since established that he was not on the receiving end of any insidious contriving; a slow-acting poison had been assumed to be Margaret’s modus operandi.

She was kind, always — maddeningly so. Preparing meals she knew he wouldn’t eat, washing the sheets every other day, humming quietly as she tidied the room he no longer seemed to inhabit with her. She’d stopped asking if he was feeling better. Instead, she would place a hand on his shoulder, just once, lightly, before retreating to the spare room with the radio on low. Not a woman terrified of discovery — but of loss.

Bounced between departments, healthcare professionals concluded Percy’s problem must be psychological.

After establishing that Percy had served in the army during the Brunei Revolt, a referral was made to Dr. Pointer, a clinical psychologist with a history of working with men suffering the after-effects of war, long after the conflict had ended.

Percy sat for a single session, forced to talk about things long forgotten, convinced to do so by an audio-tape about the subconscious’s assault on thought and subsequent behaviours, shared by his neighbour Alan, a former infantry soldier, and drinking buddy at the Duke of Wellington Arms.

"Post Traumatic Stress Disorder", the narrator said. "You may not realise", the narrator insisted.

Emerging from the session, disoriented, Percy’s thoughts were firmly fixed on the girl he killed. The remaining portion of her face. The slight smile it had. The twitching.

Breathing was laboured that day; banished thoughts had burst through locked doors and spread like vines to strangle his heart. Percy concluded that he was never going to wake in the early hours to vomit again, simply because he was unlikely to get to sleep.

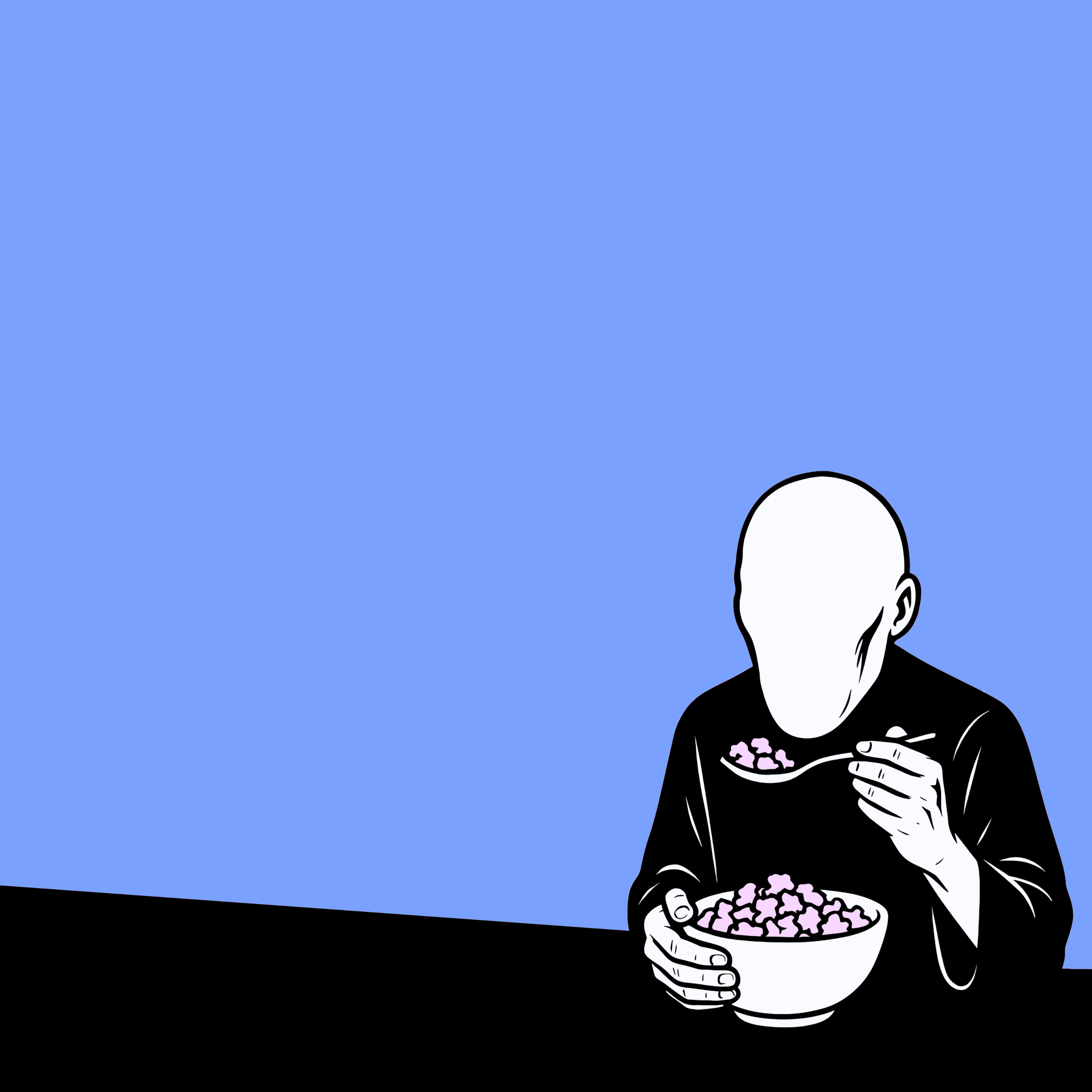

The girl greeted him when his eyes closed; the nose-down remainder of her face appeared in the mess of half-eaten food and the coming together of branches on trees at different depths.

She was everywhere.

Despite the insomnia, Percy kept finding himself waking at 2:30 a.m., and sometimes positionally compromised.

He woke on the kitchen floor, surrounded by broken glass and sporting a scalded hand on Monday, and Thursday morning he had been found by patrolling police officers on the front lawn, with an upturned rake just by his head.

Linear time had become arbitrary and needless to engage with; the sense of it passing all but disappeared along with experiential memory, unable to properly form due to the lack of sleep.

The girl with half a head, carrying in her bloodied hand Percy’s stray bullet, accompanied him everywhere he went. The girl spoke her native Malay, of which Percy understood every word.

They talked throughout his last week, mostly about Margaret. Both had concluded that she was up to no good and, as soon as she revealed herself to be so, would have to be killed.

For three days Percy supervised Margaret cooking, watched closely as she cleaned his dentures; he changed his toothbrush nightly and discarded open toiletries.

Even though he had seen nothing unusual, Percy felt confident that Margaret would have been uncomfortable with the shadowing of her every move and would think twice about continuing her insidious contriving.

Sunday night came; Percy sat quietly in the corner of the lamp-lit bedroom, half an eye on Margaret, the other on a copy of the Sunday Times he had saved for night-time reconnaissance.

He was ready to pounce, as best as old men could, into violent action; buoyed by the ghost of his guilt. Percy re-positioned the mirror on the dressing table to show Margaret’s face while she slept.

His wife had a smile, happy in her dreams, buoyed herself by the recent willingness of her husband to spend quality time with her.

At 2:25 a.m., Percy sat shaking his legs, his body and mind invigorated by the last of the adrenaline his body had in reserve after six weeks of burning the midnight oil.

Glaring at the dressing table mirror, Percy noticed something in the reflection; wisps of smoke.

A grin appeared on his face as quickly as it turned into a viscous, near canine growl.

'You think you’re clever, don’t you?' he barked.

Percy yanked open his pyjama drawer and withdrew a shirt, which he tied around his nose and mouth. Heading back to the chair he was sitting in, Percy reached behind and lifted a small garden shovel.

'Answer me, you deceitful bitch.'

Gunfire. A boat engine. He was back in Brunei and could hear the enemy singing. He couldn’t go in guns blazing. He did this before. He killed the girl, made a mess of her beautiful face.

He’d have to be calm. He’d have to take stock. Stop and think.

His eyes darted around the room; seeing no billowing smoke, Percy dropped the shovel, made his way over to Margaret’s dressing table and picked up the mirror.

He turned in a circle with his eyes on the glass, laughing, maddened by its revelation.

The smoke was visible in the reflection but not in the room. He stopped moving and stared hard at the mirage in his hands.

'Madness.', he spoke in a whisper.

Startled by movement in his periphery, Percy dropped the mirror.

With a jerk, Margaret’s stiffened body levitated from the bed and moved slowly toward the bedroom door, feet first and face down. His eyes followed the body as it floated past him at chest height.

'You always had fine, fine buttocks my love.', he quipped.

At a distance, Percy followed his wife down the stairs, straightening the family photos as he passed by and continued toward the cottage’s open front door.

A large black arthropod waited for Margaret in the street. It waved appendages along its back, wildly in a mass resembling fire, then suddenly spread in equal distance, stiff like hollow scaffold.

Through the trundling and near translucent mass, its naked female conductor could be seen from a bench on the green, reciting from an old book.

Percy waved enthusiastically and shouted,

'Fine morning for it, Janice.'

Surprised to be seen, Janice — his neighbour, still wrapped in the blanket she used for watching late-night TV — fumbled her forearms over her nipples and crossed her legs, then quickened the pace of her words.

The bench flickered at the edges, like something remembered wrong.

Women in nightgowns and baggy T-shirts floated above the creature — people Percy recognised from the post office, the doctor’s waiting room, the Wednesday craft circle — all hovering stiffly, parade-like.

The creature’s extremities opened into trumpets and sucked the women in, leaving only their heads visible.

Percy removed the pyjama shirt from his face and dropped it in the doorway of the cottage. He saluted and began to sing.

'Some talk of Alexander, and some of Hercules,

Of Hector and Lysander, and such great names as these.

But of all the world’s brave heroes, there’s none that can compare,

with a tow, row, row, row, row, row, to the British Grenadiers.'

'Those heroes of antiquity ne’er saw a cannonball,

Or knew the force of powder to slay their foes withal.

But our brave boys do know it, and banish all their fears,

With a tow, row, row, row, row, row, for the British Grenadiers.'

The smoke, invisible to Percy without the mirror, began to take him.

The view in front of him became like reflections of the scene in water, and he fell backward, hard and fast, shattering vertebrae on the ceramic tiles of the cottage’s entrance hall.

The girl with half a face appeared over him, a silhouette before the dazzling moon with the additional glow of the streetlights gently kissing her edges.

She leaned in and vomited onto his face.

'Goodnight, Percy.' she said.

And he didn’t fight it. Not this time. The warmth of it filled his nostrils, flooded his mouth, the taste bitter and ancient — like rust.

As his body stiffened, the smoke around him thickened, coating his lungs like damp fog.

He thought of the jungle. Of the girl again, whole this time. Of Margaret in her nightdress, in the garden, singing some tune from a time he couldn’t place.

In the morning, Margaret padded down the stairs, her slippers catching on the worn edges of the rug.

She paused when she saw him in the entrance hall — eyes closed, back arched strangely against the tiles, like he’d collapsed in the middle of standing.

She called his name once. Then again. He didn’t stir.

Later, the coroner would say he had drowned in his own vomit.

But Margaret, standing barefoot in the cold blue light of morning, saw something else in his expression — the faintest curve at the edge of his lips.